Human Behaviour Change: The Missing Link in Animal Practice By Hanne Grice

This raises a fundamental question: if positive change relies on human cooperation, how well are we preparing practitioners to work with the human mind?

From veterinary consultations to training sessions, shelters, grooming salons, and home behaviour consultancy visits, the interface between animal and professional is always mediated by people. Their perceptions, habits, emotional states and beliefs influence how change is received, resisted, or adopted. Understanding how people think and behave - and how to guide that behaviour constructively – is, therefore, central to our success.

The study of Human Behaviour Change (HBC) offers insight into how we can help people shift attitudes and actions in ways that support better welfare outcomes for animals. It draws from neuroscience, social psychology, communication theory, and behavioural science, fields increasingly recognised as essential in applied animal training, behaviour and welfare.

The challenge of automaticity

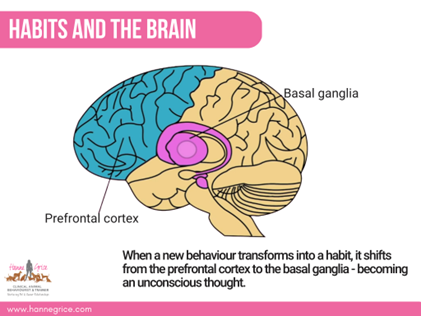

One of the most consistent findings in neuroscience is that much of human behaviour is automatic. We rely on heuristics, in other words, mental shortcuts and ingrained responses, because the brain prefers to conserve energy. Roughly half of our daily actions are habitual, shaped by repeated exposure and reinforced neural pathways.

This phenomenon, known as experience-dependent neuroplasticity, means the brain physically adapts to whatever it repeats. This has practical implications in client-facing work. For example, suppose a dog owner repeatedly responds to stress with a raised voice or physical control, such as using a lead correction. In that case, those responses become more accessible neurologically, even when they are counterproductive. In such cases, change demands excellent advice from the practitioner, and deliberate effort from the client to override their default responses, and psychological safety to form new ones.

Stress plays a pivotal role here. The amygdala, part of the brain’s limbic system, is wired to detect threat. While it evolved to help humans avoid danger in our evolutionary past, it still reacts strongly to modern-day social discomfort, such as embarrassment, perceived judgement, or fear of failing in public.

In pet-related contexts, these emotional triggers might be activated by a dog pulling on the lead in front of neighbours, or the cat refusing to be handled at the vet. While such incidents might be infrequent and minor from a behavioural point of view, emotionally, they can feel significant, influencing how clients engage with professional guidance.

The influence of belief

Beliefs act as powerful filters for information. These beliefs, about animals, professionals, or one’s own capacity, are often unconscious, yet they exert a strong influence on behaviour.

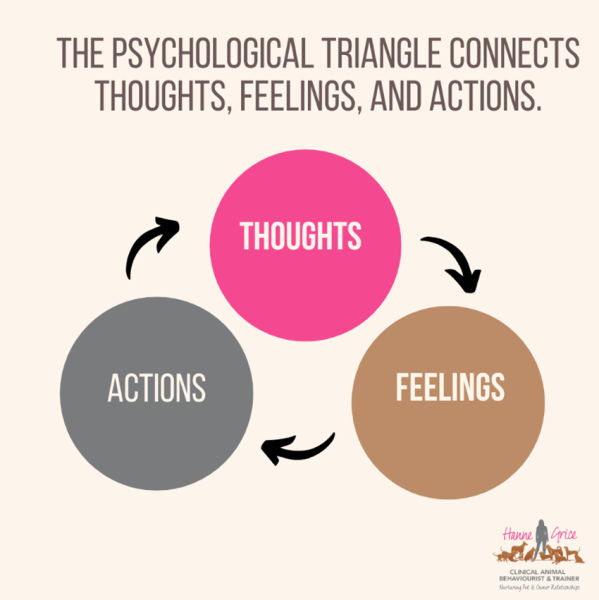

In behaviour change theory, the “psychological triangle” connects thought, emotion, and action. For instance, a client who believes they’ve failed their pet because the dog barks at others may experience shame and withdraw from seeking support from a professional. Another may hold fixed ideas based on previous experience, such as “my last trainer was no help” or “dogs like mine never change.” These assumptions shape emotional tone, limit openness, and make it harder for new guidance to be integrated.

Two key psychological biases reinforce this cycle. The reticular activating system (RAS) primes our attention to notice whatever is perceived as most relevant or threatening. If a client is embarrassed by their pet’s behaviour, they are more likely to perceive judgement in others, even where none is intended. Similarly, confirmation bias leads people to interpret events in ways that support their existing beliefs. For example, a client who is convinced their dog is stubborn may overlook progress while noticing every misstep.

Professionals are not immune to these patterns. Stereotypes about breed traits, owners’ behaviour or training histories can influence how a case is approached. Recognising and questioning these automatic filters is part of developing reflexive professional practice.

Communication as a behaviour change tool

Human Behaviour Change does not require practitioners to become therapists. However, it does require an intentional approach to communication. Active listening, open-ended questioning, and rapport-building are important behaviour change tools.

When professionals demonstrate curiosity rather than judgement, they create space for clients to be more honest and reflective. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of change. Clients who feel heard are more likely to adopt suggestions and disclose obstacles earlier.

Helping clients set clear, achievable goals further supports engagement. These may include practical tasks, such as installing visual barriers to reduce barking, or emotional milestones, such as feeling confident enough to advocate for their animal in a public space, like telling the stranger to stop petting their dog’s head as he needs space. These small steps make the path to change more tangible and reduce the sense of overwhelm that can derail progress.

Follow-up is also essential. Behaviour change in both humans and animals is rarely linear. Regression is common. The challenge is not avoiding setbacks but managing them constructively. When clients understand that fluctuations in progress are expected, they are less likely to abandon the process altogether.

Addressing limiting beliefs

Limiting beliefs, convictions that constrain what a person believes is possible, are a major barrier to progress when it comes to successful behaviour change. Limiting beliefs might include ideas such as “I’ve already tried everything,” or “this won’t work for us.”

Such beliefs often originate as protective mechanisms. They shield the person from disappointment, shame, or social discomfort. They also reduce openness to new ideas. In behaviour change work, one helpful strategy is known as “deliberate behaviour modelling.” This involves encouraging clients to act as though a different belief is already true. For example, instead of assuming a dog cannot learn recall, the client is supported in practicing short, strategic recall sessions in a controlled environment. So, when their pet’s behaviour begins to shift, their belief does too.

This is particularly important in addressing the self-fulfilling prophecies that undermine progress. When someone believes a plan won’t work, they are less likely to engage fully, which reduces the chance of success and reinforces their original assumption. When professionals help clients see this loop in action, it can be enough to create a shift.

Another challenge to successful HCB is the Dunning-Kruger effect – first described by David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999 – this is a cognitive bias where people with limited experience overestimate their knowledge. A client may have raised the same dog breeds in the past and arrive with strong views about “what works.” This perceived expertise can make it difficult for them to accept alternative strategies. As professionals, we can gently challenge overconfidence by inviting reflection: “How did that approach work last time?” or “What made you decide to seek support now?” Framed with respect, such questions encourage insight rather than defensiveness from our clients.

Motivation, mood, and emotional contagion

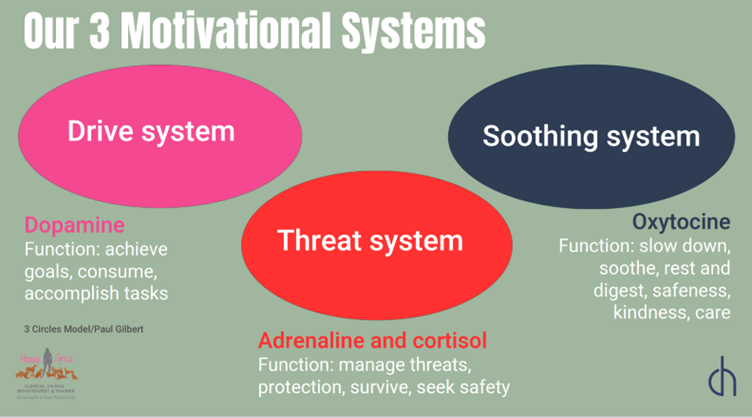

Understanding motivation is also essential in HBC. Paul Gilbert’s model of motivational systems, highlighted in his 2009 book titled The Compassionate Mind: A New Approach to Life’s Challenges, suggests there are three emotional drivers. These are: the threat system, the drive system, and the soothing system.

Many clients operate in a state of threat-fuelled drive, motivated to act, but from a place of fear or guilt. While this may produce short-term effort, it’s emotionally costly and unsustainable.

By contrast, when motivation is supported by the soothing system, such as a desire to improve the relationship with the animal, clients tend to be more resilient. Setbacks are less likely to derail progress, and emotional energy is preserved.

Emotions are also socially contagious. The concept of emotional contagion, supported by research into mirror neurons, shows that humans and animals can catch each other’s mood. Dogs, for example, are known to respond emotionally to the affective state of their guardian. A stressed client may, therefore, inadvertently contribute to the stress of an animal, creating a feedback loop that hinders learning and welfare.

For this reason, helping clients manage their emotional state is not ancillary to behaviour work, it is a direct contributor to outcomes. Simple practices, such as guided reflection, setting boundaries, or reframing expectations, can shift the emotional tone of the consultation or training session and improve results for both the client and the animal.

The professional benefit

Understanding HBC supports practitioners by providing frameworks to interpret challenging client, employer or peer behaviour more objectively. By having greater awareness of the factors that drive resistance and a lack of cooperation, animal professionals can reduce their feelings of frustration and avoid internalising lack of client follow-through as a personal failure, which can otherwise lead to self-doubt, including feelings of imposterism. In a field where emotional labour is high, having these professional skills serves a protective function.

Develop the skill set – Human Behaviour Change for Animal Professionals Course

Despite the clear relevance of HBC, many training, welfare and animal behaviour courses provide minimal coverage of the psychological and communication components involved in working with clients.

In response to this gap, I developed a modular online course in Human Behaviour Change, recognised by the iPET Network, and worth 15 PDR points. The course offers structured training in rapport-building, communication, bias, motivation, and belief systems. It includes case studies and has been specifically designed for animal professionals across disciplines, from behaviourists and trainers to veterinary staff and animal welfare workers.

The goal of the course is simple: to equip animal professionals with the tools they need to work more effectively with others, thereby improving the animal’s welfare. When clients feel understood, they are more likely to act. When that happens, animals benefit and you stand out from the crowd as a professional that delivers outstanding service and ‘gets’ their clients.

To learn more about the Human Behaviour Change for Animal Professionals course, visit Human Behaviour Change for Animal Professionals

Hanne Grice is a certified Clinical Animal Behaviourist, trainer, lecturer and educator. She has over two decades of experience in companion animal behaviour, training and applied psychology.